Updated 26/08/2020

I have previously discussed the effect of Edward Bernays on public relations and corporate advertising. He famously ushered in the acceptance of taboo products by engaging with the public on an emotional level, appealing to their irrational impulses rather than their critical sensibilities. One such taboo product was instant cake mix; so ignored by consumers because there was an irrational guilt associated with hastening a process that was traditionally seen as caring and unique. Bernays achieved this by altering the recipe to include an egg, thereby infusing the task with the missing construction element that made it personal and valuable.

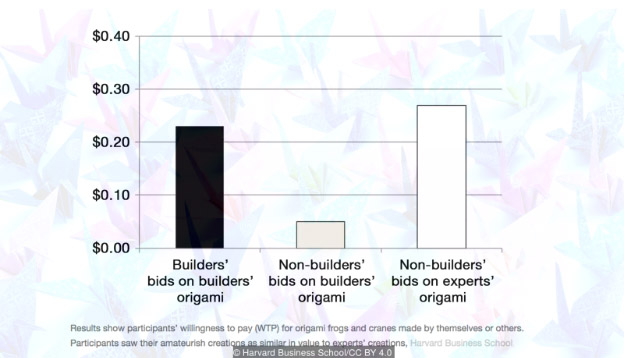

This kind of manipulation that leads to the consumer placing a higher value on the product is termed the ‘IKEA effect’. So named due to the specific study that investigated consumer valuation of IKEA products, this effect leads people to believe that their personally constructed items (even those outside of IKEAs range) have as much value as an item assembled by an expert in the same field. This was true even in other potentially highly skilled fields such as origami and even Lego building.

This seems like a fantastic opportunity for a company to exploit this tendency. Simply involve your customers in some part of the process and you will get a free boost in perceived value. A quick browse in the supermarket (and online) in the last few years would reveal a growth in the ‘food kit’ phenomenon, where all the raw ingredients are prepared and cut for the customer to put together in the pan and take all the credit. Anyone old enough to remember the Airfix kit and the birth of Warhammer 40,000 will realise there is a healthy market and huge customer evangelisation to be found when the personal touch is required.

However, the IKEA effect is a double edged sword (or screwdriver). The wider lesson is that estimation of everything we make is higher than other people would value, and that includes your product/service as a business. Maybe your pricing is based on your understanding of the sacrifices you made to make your product a reality, and therefore you overestimate its potential value to customers. Often a product or service is developed to solve a particular problem that the inventor had but that nobody else thinks is significant (how many Segways or Sinclair C5’s do you see? Know anyone with a Juicero?). It could also be that you know how to use your service after years of familiarity but that your customers have no idea how it works.

Think this doesn’t apply to you? As with many cognitive biases that I will cover in the series, those who think they are immune are most likely to demonstrate the symptoms. This is especially true in the next article in the series, where I will be looking at the Dunning-Kruger effect.

This seems like a fantastic opportunity for a company to exploit this tendency. Simply involve your customers in some part of the process and you will get a free boost in perceived value. A quick browse in the supermarket (and online) in the last few years would reveal a growth in the ‘food kit’ phenomenon, where all the raw ingredients are prepared and cut for the customer to put together in the pan and take all the credit. Anyone old enough to remember the Airfix kit and the birth of Warhammer 40,000 will realise there is a healthy market and huge customer evangelisation to be found when the personal touch is required.

However, the IKEA effect is a double edged sword (or screwdriver). The wider lesson is that estimation of everything we make is higher than other people would value, and that includes your product/service as a business. Maybe your pricing is based on your understanding of the sacrifices you made to make your product a reality, and therefore you overestimate its potential value to customers. Often a product or service is developed to solve a particular problem that the inventor had but that nobody else thinks is significant (how many Segways or Sinclair C5’s do you see? Know anyone with a Juicero?). It could also be that you know how to use your service after years of familiarity but that your customers have no idea how it works.

Think this doesn’t apply to you? As with many cognitive biases that I will cover in the series, those who think they are immune are most likely to demonstrate the symptoms. This is especially true in the next article in the series, where I will be looking at the Dunning-Kruger effect.